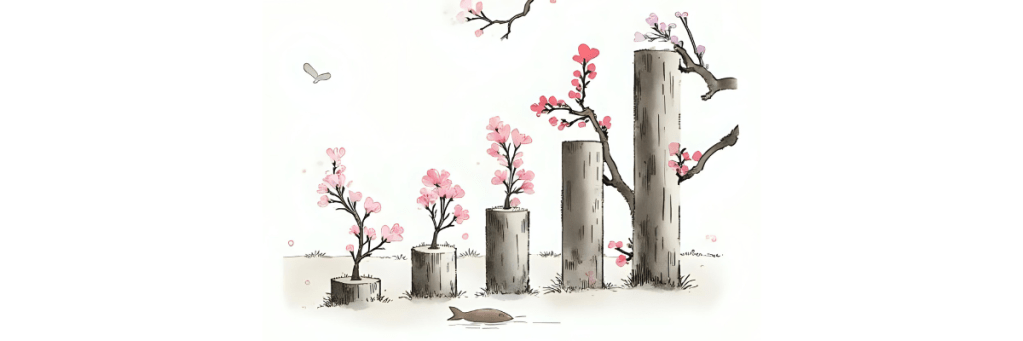

Focus on minimising risk to significantly enhance your long-term investment performance.

Equity investors aspire to achieve superior investment returns from the stock market, for which they must execute two tasks effectively: 1) Stock Selection, and 2) Portfolio Construction. Although both activities are equally important, ‘portfolio construction’ seldom receives the attention it deserves.

Most investors are unaware of the negative impact that neglecting portfolio construction could have on their investment performance. When things go wrong, they blame the markets or their portfolio stocks. Acknowledging the significance of portfolio construction in your investment performance and thus committing time and effort to it is essential for consistently achieving superior investment results.

An efficient portfolio is optimised for maximum return at the least possible risk. Through stock selection, we intend to maximise returns; through portfolio construction, we aim to minimise risk. Defence should be the strategic objective behind investment portfolio construction: protecting against earnings slowdowns, corporate missteps, economic downturns, increased market volatility, changing economic conditions, poor judgments, and incomplete information.

Diversification is an investment concept closely associated with portfolio construction (and management). It gained prominence as a risk management strategy in the 1950s through the modern portfolio theory (MPT). According to MPT, by constructing a diversified portfolio with many stocks, investors can mitigate the risk associated with individual stocks. Thus, the overall portfolio risk is much lower than the sum of the risks associated with individual stocks comprising the portfolio.

The larger the number of stocks in a portfolio, the more diversified it is, thus the greater the risk reduction. Empirical studies have shown that a portfolio comprising 40 to 50 stocks can reduce overall portfolio risk by almost 60 per cent. However, the addition of stocks beyond 50 is found to have a negligible impact on risk.

Not everyone is a proponent of diversification. Warren Buffett, considered the world’s greatest investor, does not favour a diversified portfolio. “Only those who don’t know what they are doing favour a diversified portfolio,” he states. He believes in holding a concentrated portfolio of high-quality stocks bought at reasonable valuations with a long-term perspective.

The problem with diversification is that, while it reduces risk, it also limits a portfolio’s return potential. If a stock in a 50-stock portfolio doubles in a year, it contributes only 2 per cent to the portfolio’s overall return.

AMN Capital is an equity-oriented investment firm aiming to achieve superior investment returns from an investment portfolio of Indian publicly listed equities. When the fund’s capital is not fully invested in equities, it is held as cash, short-term deposits, or units of money market funds.

We prefer neither a diversified portfolio of 40 to 50 stocks nor a highly concentrated portfolio of 5 or fewer stocks. A fully invested portfolio of 10 to 15 stocks seems appropriate for us; this way, the portfolio’s exposure to any single stock is limited to 7.5 to 10 per cent. However, this is more than just a risk management strategy: we can effectively follow only 10 to 15 stocks at a time.

In addition to individual stock risks, there are risks associated with specific industries. If industries face challenges such as increased competition or a demand slowdown, all companies within the industry would be adversely affected to varying degrees. A stock-wise diversified portfolio may sometimes be concentrated in a single industry if it contains several stocks belonging to the same sector. A portfolio’s industry-wise risk could be diversified away just the same way as its stock-wise risk is diversified away. Limiting a portfolio’s exposure to a single industry to less than 25 per cent seems an appropriate investment policy.

Some industries that appear distinct superficially might be interrelated on a deeper level. Such interrelations between two or more industries should be assessed during portfolio construction.

Consider two stocks: a chemical and an auto parts manufacturer. We believe both belong to separate industries. However, a deeper glance reveals that the chemical manufacturer’s principal product is a vulcanising agent used in tyre manufacturing. Therefore, the chemical manufacturer’s business is closely related to the tyre industry, which in turn is closely related to the automotive industry. Thus, these two stocks (the chemical and auto parts manufacturer) should be grouped into a single industry segment (automotive) while evaluating risk during portfolio construction.

The right stock has strong fundamentals, a reasonable valuation, and a positive earnings trend. The most advantageous buying opportunity occurs when all three conditions are met simultaneously. Unfortunately, such opportunities are rare. Waiting on the sidelines until such opportunities emerge would be counterproductive to our investment performance.

Suppose you find a stock with strong fundamentals and a reasonable valuation which trades at ₹100 per share. However, its earnings trend is negative. So, you decide to wait until the earnings trend turns positive before purchasing the stock. Say, two quarters later, the earnings trend turns positive. However, the issue is that the stock now trades at ₹300 per share. Although disheartening, you buy the stock, nevertheless. The positive earnings trend continues for two more quarters, but the stock price remains unchanged. However, in the third quarter after your purchase, the earnings trend turns negative, and the stock declines to ₹200 per share in a month. This is a classic case of buying high and selling low—a common mistake committed by many investors.

Such perplexing and disappointing stock behaviours happen too often in the markets. The problem is not with the markets but with our understanding of them. Among the three criteria of a right stock, only fundamentals have longevity; valuation changes, although gradual; however, earnings trends can be volatile and uncertain. We risk compromising our investment performance by basing our investment decisions solely on a stock’s earnings trend.

Stocks eligible for addition to our investment portfolio must have strong fundamentals and a reasonable valuation (market price close to or less than their intrinsic value). If valuation is reasonable, the downside risk is limited; the adverse impact of an unfavourable earnings trend on the stock’s price is also restricted. Moreover, the stock’s upside potential is greater if the earnings trend turns favourable.

The problem is when a stock’s valuation is elevated, despite robust fundamentals and a positive earnings trend. It happens when the stock’s market price has run too far ahead of its intrinsic value. Holding onto the position seems appropriate if the earnings trend remains positive. However, with higher downside risk now, an earnings slowdown could be a significant drag on the stock price. Therefore, limiting such stock’s portfolio exposure to less than 10 per cent would be prudent. Moreover, as soon as the first sign of an earnings slowdown appears, the respective stock position should be reduced, either gradually or rapidly, as the situation demands, to less than 2.5 per cent of the portfolio. Completely exiting the position is also advisable, despite the robust fundamentals.

Regularly reviewing the performance of our portfolio and the individual stocks that comprise it is essential for achieving our investment objectives. Areas where performance deviates from the objective should be carefully evaluated. Valuable feedback from such evaluations should be incorporated into our investment policy and process.

The portfolio performance should be reviewed against a benchmark. Inflation, risk-free assets, and major market indices are effective benchmarks for evaluating portfolio performance.

Due to inflation, money loses its purchasing power over time. A four per cent inflation means a product you purchased for ₹1,000 last year would cost you ₹1,040 this year. Your money should grow by at least the inflation rate to maintain its purchasing power. If you had invested your money in an asset that delivered a 5 per cent annual return while inflation was running at 7 per cent, it means your money’s real worth has decreased by 2 per cent during the year. Your investment portfolio effectively preserves your wealth only when its return outpaces the inflation rate.

Equities are one of the riskiest asset classes. Rational investors will invest in equities only if they offer a prospective return commensurate with their risk; higher risk should be accompanied by higher return prospects. Today, virtually risk-free assets, such as the Indian government’s 10-year bonds or the State Bank of India’s fixed deposits, promise returns ranging from 6.25 to 6.55 per cent per annum. To maintain investment appeal among investors, equities should provide a return at least 50 per cent higher than the risk-free return; presently, that would be around 10 per cent.

We (AMN Capital) focus mainly on micro stocks, whose market capitalisation ranges from ₹100 to ₹2,000 crores. These stocks have a significantly higher risk than the index-forming large-cap stocks. Therefore, our risk-commensurate expected average annual return is 18 to 20 per cent, almost double that of general equities.

Major market indices, such as the Sensex and Nifty 50, comprise stocks of large, leading companies from the major industries of the Indian economy. Different companies have varying weights in these indices according to their size and importance. Index funds are low-cost, passive mutual funds whose managers aim to replicate the returns of major market indices by buying stocks that comprise these indices. Each stock’s weightage in the index fund will be the same as its weight in the market index.

The passive fund manager does not analyse individual stocks to determine their investment prospects. He simply buys the index stocks, regardless of their fundamentals and valuation. These funds have very low costs due to the minimal skill and effort required for their portfolio construction.

We are active managers. Active managers search the entire universe of investable stocks to identify opportunities with superior return prospects. He analyses an individual stock’s industry, business, financials, and valuation to determine its investment prospects. Active managers have higher fees than passive managers. So, their performance should also follow suit.

As a passive manager can imitate the benchmark return without any of the active managers’ efforts, an active manager’s job is valuable only if he can beat the benchmark market indices. An investor can achieve market returns by purchasing low-cost index funds. Active managers must outperform market indices to attract and retain investors. Consistent outperformance is the cornerstone of active management.

In conclusion, an actively managed investment portfolio should beat the inflation rate, sufficiently outpace the risk-free return, and consistently outperform major market indices.

Effective portfolio management leads to increased financial wealth, which in turn contributes to enhanced future spending power. However, the trouble with the future is that it is always in the future. It is 2025 now; 2030 is in the future. However, five years later, as 2030 arrives, it is no longer the future: it is the present, and 2035 is the future then.

You never get to experience your wealth if you always preserve it entirely for the future. Effective portfolio construction and management should include an appropriate distribution policy. Every year, a portion of your investment portfolio should be distributed to meet present spending needs.

An effective distribution policy allows you to enjoy the rewards of effective portfolio management without impeding the portfolio’s ability to enhance future spending power. Distributing five per cent of your investment portfolio seems an effective distribution policy. This may have to be revised up or down according to your portfolio’s investment performance each year.

Suppose you had a ₹10,00,000 investment portfolio that returned 12 per cent annually for five years. At the end of the first year, your investment portfolio would be worth ₹11,20,000. Under a five per cent distribution policy, ₹ 56,000 could be distributed; the post-distribution investment portfolio would then equal ₹10,64,000. Likewise, at the end of the second year, with a 12 per cent annual return, the investment portfolio would be worth ₹11,91,680; now, 59,584 could be distributed; the post-distribution investment portfolio would equal ₹11,32,096. As you can see, the size of your investment portfolio and the amount distributed increased each year. This should be the intention behind an effective distribution policy.

Subscribe

Subscribe to receive our latest content directly in your inbox.