Stock returns are expected to trail earnings growth over the next decade.

The economic environment during the forty years from the early 1980s until 2022 was characterised by low inflation and declining interest rates. From the high teens in 1980, interest rates in developed countries declined for nearly 28 years. They reached near zero in December 2008 at the depth of the global financial crisis and stayed near zero for most of the next fourteen years.

Since declining from 14 per cent in 1980 to less than 3 per cent in 1983, there has been no severe inflation situation in the developed world for more than 40 years, other than a short-lived spell in 1989-1990 consequent to the Gulf War.

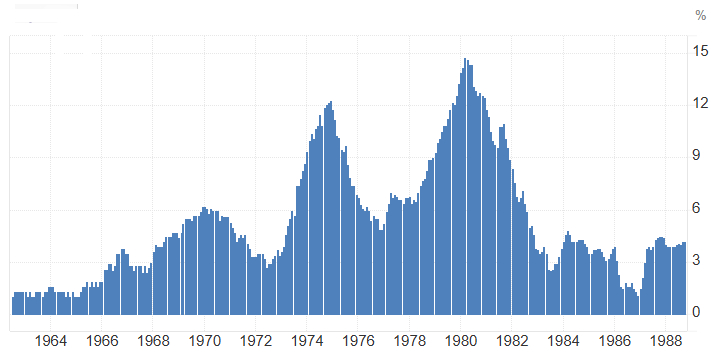

The last major case of severe inflation in the developed world happened around the 1970s. In the US, as evident from the figure below, it lasted twenty years and had three episodes of rise and fall, with each successive episode having a steeper rise and fall than its predecessor. Each episode lasted for four to five years.

During the first episode, inflation increased from 2.7 per cent in November 1967 to 6.2 per cent in December 1969 and then declined to 2.7 per cent by June 1972. During the second episode, inflation increased from 3.4 per cent in October 1972 to 12.3 per cent in December 1974 and then declined to 4.9 per cent by December 1976. During the third episode, inflation increased from 6.5 per cent in April 1978 to 14.7 per cent in May 1980, declining to 2.5 per cent by July 1983.

Meanwhile, US interest rates were 4.00 per cent in 1965 at the beginning of these severe inflation episodes. They increased and topped 20 per cent in 1980-1981 and later declined. By 1985, when the severe inflation was finally subdued, interest rates were near 8.00 per cent.

The key takeaways from the severe inflation of 1965 – 1985 were:

- The inflation had more than one episode of rise and fall.

- The rise and fall would be steeper in each subsequent episode.

- Interest rates will move alongside the inflation trajectory.

- Interest rates at the end will be greater than at the beginning.

We recently had a serious inflation bout during 2021-2023, when inflation in the US increased from 2.6 per cent in March 2021 to 9.1 per cent in June 2022 and then declined to 3.0 per cent by June 2023. The bout lasted two years and three months, much shorter than the inflation episodes of 1965-1985. However, this might be our first major experience of a serious inflation bout since the 1970s.

The European Union and the UK experienced a similar spike and retreat in inflation around the same time. The central banks of these developed countries increased interest rates steeply to tame inflation, and those measures were effective because inflation in these countries has (almost) retreated towards their central banks’ target range. Today, most of these developed countries’ central banks have cut rates at least two or three times this year, and more rate cuts are anticipated next year.

The rate cut actions were made under the impression that the inflation threat is largely quelled, and hence, economic growth could now be prioritised over inflation. But as we saw in the 1970s, the 2021-2023 inflation bout might be the first episode in a series of inflation bouts, with the rest of the episodes to follow soon.

Diminishing trust in globalisation which has emerged in recent years, increasing geo-political tensions, and the adoption of restrictive and punitive trade measures by newly elected governments have increased the likelihood of more episodes of severe inflation in the coming years. Again, as we saw in the 1970s, the upcoming episodes could be more severe than the 2021-2023 episode.

Interest rates declined from the double digits of the early 1980s to near zero in 2008 and stayed there for a long time. However, they were raised steeply due to the inflation spike of 2021-2022. Once it hits zero, the obvious future direction of interest rates should be higher.

We had an economic environment characterised by declining interest rates for almost twenty-eight years (1980 – 2008), and afterwards, we had one characterised by extremely low interest rates for nearly thirteen years (2008 – 2021). Interest rates began to rise from 2022 onwards indicating that the interest rate cycle has reversed. High and rising interest rates would characterise the coming decade’s economic environment. The environment would also be characterised by frequent bouts of inflation, which could be the force driving interest rates higher.

High inflation and rising interest rates are unfavourable for stocks. Investors’ current investment approach has been shaped by and suited to the economic environment of the past four decades, characterised by low interest rates and low inflation. Those approaches might have been effective then but are unlikely in the new emergent economic environment of high inflation and rising interest rates. Building a portfolio that is resilient and outperforms in an inflationary environment is the biggest challenge for today’s equity investors.

How do we (investors) prepare us and our portfolio for a high inflation – high interest rates environment?

Large and popular stocks like those belonging to major market indices will struggle in the new environment. These stocks have robust fundamentals, established business models, and thus, more certain earnings prospects. Due to this high certainty, their earnings for a long time are discounted into their current market price. When interest rates rise, the present value of these long-term future earnings streams will be greatly reduced as they are now being discounted at a higher rate. Consequently, the stock prices of these companies will decline to reflect the reduced present value.

In essence, there will be a moderation in valuation, and stock price returns will significantly lag earnings growth. The higher the valuation now, the greater the lag and underperformance later. Valuation will be increasingly prominent in deciding a stock’s investment performance in an inflationary environment.

Stocks with less present earnings but high anticipated future earnings (growth stocks) will greatly suffer. Stocks with reasonable present earnings and profitability but not much in the form of anticipated future earnings (value stocks) will likely flourish.

A firm committing to capital expenditure seems agreeable when interest rates are low because of the low opportunity cost and the future revenue accrual the capital expenditure promises. However, capital expenditures are less agreeable when interest rates are higher due to the higher opportunity cost and the reduced importance of future earnings relative to present earnings in an inflationary-high interest rate environment.

Deleveraging, or retiring outstanding debt, is preferable because its positive impact on the bottom line increases as interest rate increases. Firms that pay dividends will gain favour among investors because dividends are cash paid out from present earnings, which are more relevant than future anticipated earnings in an inflationary environment.

Some of the expected moderation in valuation seems to have materialised over the past two years. Asian Paint’s price-earnings ratio declined from 100 two years ago to 50 today, during which its earnings increased by 50 per cent. Bajaj Finance’s price-to-book value shrank from 12 to 5 over the past two years: meanwhile, its earnings doubled during the two years.

Pidilite Industries’ earnings increased by 60 per cent while its price-earnings ratio declined from 100 to 80; ICICI Bank’s stock price increased by 47 per cent, its earnings rose by 88 per cent, and the price-to-book value remained stable at 3.5.

Hindustan Unilever’s earnings increased by 15 per cent while its price-earnings ratio moderated from 70 to 55; Titan Industries’s earnings doubled while the price-earnings (PE) ratio moderated from 140 to 90.

The anticipated pattern of stock price returns lagging earnings growth and moderation in valuation is conspicuous in all the above instances. However, there seems to be more left of this trend because, despite the valuation moderation of the past two years, the valuation of many stocks remains much elevated relative to their long-term averages.

Hindustan Unilever trades at a PE of 55 today compared to its long-term median PE of 47.9. Titan Industries trades at a PE of 90 today compared to its long-term median PE of 54.8. Pidilite industries trade at a PE of 80 today compared to its long-term median PE of 48.5. Asian Paints today trades closer to its long-term median PE of 48.6.

However, the long-term median PE values themselves must adjust downwards as interest rates increase. The prevailing long-term median PE values were formed during the low interest rates environment of more than a decade after the 2008 global financial crisis. This trend of valuation moderation and stock price returns trailing earnings growth will continue for at least the next decade, characterised by occasional inflation bouts and higher interest rates.

Subscribe

Enter your email below to receive our latest content in your Inbox.